I have written a few posts about the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and, in doing so, I have become aware of a number of myths that are linked to it. These are worth challenging because they get in the way of us taking anything useful from these results. The myths are:

1. We should look to Finland as an exemplary education system

Hardly a month can go by without a glowing newspaper article about education in Finland. This is a worldwide phenomenon. For instance, a December 2016 piece in the Hindustan Times suggests that India should copy Finland’s new cross-curricular approach to teaching. Sometimes PISA is not even referenced in these articles. Yet any search for the source of the idea of Finland as an education powerhouse takes us back to Finland’s performance in PISA in the early 2000s.

Some of this is logically baffling. Finland haven’t yet fully implemented phenomenon-based learning – their new cross-curricular approach – and so it can’t possibly be the cause of high test scores more than ten years ago. Perhaps we are basing our views on trust: they must know what they’re doing so this new reform will work. Yet this is a very shaky idea, particularly given that Finland has significantly declined in PISA since the start of the century:

These scores (which I’ve averaged across Reading, Maths and Science) are PISA’s best attempt at creating a measure that means the same thing in different rounds of the test. A score of 530 in 2000 should therefore reflect the same level of knowledge and skills as a score of 530 in 2015. In reality, it’s not a simple as this because it is difficult to compare between different tests. However, the evidence does seem to indicate an absolute decline in Finland’s performance. In other words, Finland isn’t slipping simply because it is being overtaken by other countries, it is slipping because of a decline in knowledge and skills in Finland.

If we want to look to Finland as an example then we should be looking at their education system prior to about 2000. Given that PISA tests 15-year-olds and that PISA test questions tend to have a heavy reading load (more later) then we should probably also go back considerably further than 2000 to look at what was happening when these children were in primary school. Any reforms taking place since the early 2000s could actually be the cause of Finland’s decline and yet it is these reforms that edu-tourists see when they visit Finland and that generate breathless newspaper reports. The education system in Finland is not stable and many of the features that are trumpeted in the press are not likely to be associated with the performances of the early 2000s. Tim Oates has written an excellent piece about this which is worth reading.

In my view, it is generally more insightful to look at the trajectory of a particular country or region than to compare between different countries. Finland is small and relatively homogeneous. It is unlikely that it is feasible to replicate its system in a larger and more multi-faceted country such as the U.S. or India. The same argument also applies to Shanghai, Singapore or any of the other stand-out countries. Instead, rather than trying to copy the features, we should be looking at how countries have lost, gained or maintained ground over time and what practices are associated with this.

PISA also offers us some insight into practices that are linked with higher performance within individual educations systems and this leads us to the next myth.

2. Math Students From High-Performing Countries Memorize Less

This claim is quite catchy and fits with the fashionable constructivist view of maths teaching promoted by Dan Meyer, Jo Boaler and others. It originates in a 2016 report aimed at maths teachers and based on the 2012 round of PISA testing. It was further fueled by an editorial in Scientific American. The problem is, I can find no evidence to support it.

PISA created a very odd measure of memorisation. Normally, when assessing attitudes, researchers tend to use a Likert scale so that subjects can indicate the degree to which they agree with a particular statement. However, for PISA’s measure of memorisation, they forced students to choose one of three options, potentially magnifying the effect of a weak or even non-existent preference. From this survey, they created an ‘index of memorisation’.

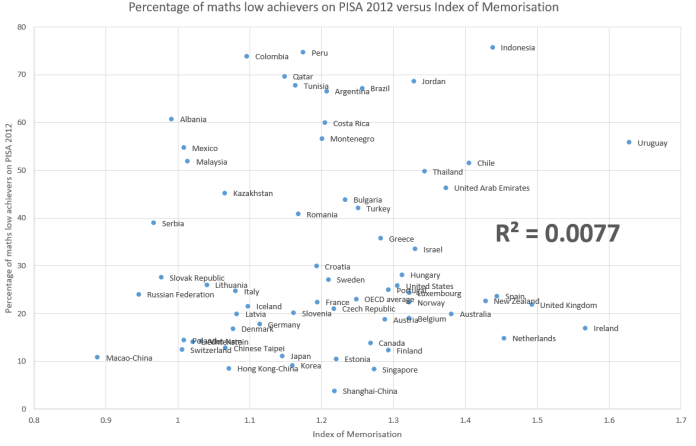

If you plot the scores of each country on this index against their PISA 2012 maths score there is no correlation at all:

The claim made in the Scientific American piece is actually a little more subtle:

“In every country, the memorizers turned out to be the lowest achievers, and countries with high numbers of them—the U.S. was in the top third—also had the highest proportion of teens doing poorly on the PISA math assessment.”

This essentially relates to data that is not publicly available. We don’t know what proportion of students in each country were classified as ‘memorisers’. Instead, we have the memorisation index. However, it seems unlikely the number of memorisers in any given country would not correlate closely with the score on the memorisation index. If you plot the proportion of low achievers in PISA 2012 maths against memorisation index then, again, there is no correlation:

Until and unless data on the number of memorisers is released then I think we have to judge this claim as unproven and unlikely.

3. PISA is just a multiple-choice test of factual recall and so it can be dismissed

Some people are not keen on the findings of PISA at all. On social media I often see it dismissed, particularly in response to any evidence I present from the programme. Some people seem to assume that, in principle, multiple choice tests can only be tests of factual recall; which is obviously wrong. And while PISA does use multiple choice, it also uses other forms of questions.

In fact, the folks behind PISA are much more interested in application of ideas than factual recall. This means they need to describe a context and this leads to the pretty high reading load of PISA test questions. I understand that the maths questions are based upon the Realistic Maths Education philosophy from the Netherlands – a constructivist approach.

It’s worth taking a look at some of the test items that PISA make publicly available. For instance, this science question is quite complex and is about conducting investigations. It is not a test of recall and it is not multiple choice.

Things that are true but that you won’t hear about

Oddly, there are some very clear findings in PISA that don’t seem to garner much publicity. In 2012, students were surveyed on the extent to which their maths lessons had a ‘student-orientation’; which roughly maps onto ideas that might be described as constructivist or child-centred (yes, I know that all teaching is child-centred but this term is also associated with a specific set of facilitative teaching practices). There was a strong negative correlation between the index of student-orientation and maths performance – the more student-oriented the learning experience, the worse the maths performance. This was true when looking within individual countries and so was not due to different cultural factors. PISA also surveyed students on other maths teaching experiences and found some interesting results, but nothing as strong as the one for student-orientation.

We saw a similar pattern when the PISA 2015 data was released in December. This time, the focus was on science and so PISA surveyed students on the degree to which their science lessons were ‘enquiry-based’. Again, this is essentially a measure of constructivist or child-centred teaching and, again, it correlated negatively with scores in the highly application-based PISA science test, suggesting that if you want students to be able to apply scientific principles, you might want to avoid enquiry-based learning.

You can speculate as to why these findings have not been promoted as much as the myth about memorisation but I think a hint might be that PISA define good teaching as being student-oriented.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Pingback: Les miracles de la Finlande! L’analyse monte ici un déclin des performances avec leur réforme!!! | Le Soutien au Comportement Positif (SCP) au Canada

Reblogged this on From experience to meaning… and commented:

An interesting and well-documented post by Greg!

As a more vague “myth” there seems to be a conception in the educational community that absolute score or rank suffices to indicate whether a school system provides a model worth examining. I think this is erroneous.

There are numerous conflating factors that weigh, perhaps overwhelmingly, into a country’s absolute score. Socioeconomic indicators and family culture, to name two, are extremely difficult to account for, and may behave unpredictably, making the accounting for such things and the covariance analysis fraught with difficulty, even impossible.

I believe of much more value is the drift of that score over time. PISA is a policy analysis tool — the point is to see the EFFECT of policy. So one must look to the changing performance of a school system and related it, not so much to STATIC elements in a school system, but to those that are CHANGING. I have seen very little analysis of this type in the popular educational chatter-sphere. But it is the primary aspect of PISA worth considering.

A good case in point is the 9-year 30-point decline in Sweden, which the OECD wrote about after the 2012 PISA. There were, indeed, some dramatic changes in teaching in that country during that period, and finding likely culprits was not particularly difficult (separating those that had the most likely impact was something of a greater chore).

Further, PISA is a lagging indicator. Something done 10 years ago in the school system may take most of those 10 years to show in performance at the 15-year-old level where PISA picks it up. Further, since PISA is administered only once every 3 years, it may be picked up only well after a decade of whatever it was that took place. Further, some kinds of educational intervention take some time to stabilize. An influx of dollars for changing teacher-to-student ratio, for example, might not show benefits until the system has absorbed the new staff and learned to take advantage of the change. I saw this up close in the late 1990s in California as they moved to significantly reduce class sizes in EVERY Primary-Grade class in the state. The problem was that this demanded many thousands of new teachers. Guess what? You can’t train that many teachers overnight. I heard — and saw — numerous tales of woe as inexperienced, poorly trained, or low-grade teachers were moved into classrooms. Further, there was insufficient space to accommodate all the new teaching spaces required. In Fresno-Clovis they “invented” a school overnight, out of portable buildings, and bussed kids from all over the city to it. The teachers involved worked heroically, but it is hard to overcome the logistical and bureaucratic nightmares that this entailed.

People looking to Canada, Finland, and the orient should pay careful attention to the drift of scores over time. Canada remains a top-performer in terms of rank. But note the decline. Indeed, some of the policy changes during that same 9-year period are similar to those in Sweden and have had similar effects. So looking to “high ranked” Canada and noting that policy X is in place may not be of much value. Indeed, what if that policy was not in place 10 years ago and is largely responsible for the 20-plus point drop in performance?

Finally, one must understand that most of the nations in PISA reports are not educational monoliths. In Canada we have 10 provinces with functionally distinct education systems — the most distinct of all being that of Quebec. Now Quebec’s scores did well over that decade – a slight drop followed by a slight rise. But the other provinces did much more poorly. This information does not appear in the international report (you can find it in Annex B2, however!), but it does appear in the Canadian report … and the news about Canadian MATH scores is not particularly good.

The problem is that Quebec has done fine … and it is a very large province, population-wise. So Quebec’s score functions as a smokescreen to what is going on in the rest of the country — unless you look at the provincial benchmarking.

Another case in point is British Columbia, in which some 10% of schools use JUMP Math, an excellent and properly-structured instructional resource which consistently outperforms the commercial resources being used elsewhere. With that many schools using superior materials there will be a muting effect on the drift of BC scores. Indeed, while BC has drifted downwards, like the other 7 provinces using the WNCP curriculum, it has not dropped as dramatically as others. Could the widespread use of JUMP Math account for this? We don’t know — it’s not in the PISA data.

Two provinces in particular did quite poorly. Alberta, which is STILL a “top performer”, is the lead province in developing WNCP … and they dropped badly. While Sweden’s drop of 30 points over 2003-2012 was the worst among NATIONS, Alberta’s PISA score dropped by 32 points! That Alberta is a “top performer” even today is a testament to how well it did BEFORE implementing WNCP — not to its current state of affairs. The Atlantic provinces, a few years later, began adopting local versions of WNCP. Why? Because “it’s Alberta’s curriculum”. There’s the problem.

Manitoba dropped even further — 36 points — after implementing the WNCP curriculum. In 2003 Manitoba performed slightly above the Canadian average. By 2012 the province had dropped a long way, to the second-last position only slightly ahead of the caboose, PEI. However, a year or two earlier PEI had just re-implemented standardized testing across three grades. While there was no sign of any effect in the Grade 10s that wrote PISA in 2012, a year later their Grade 8s leaped in performance to around the Canadian average in the similar PCAP assessment. Could the standardized testing account for that change? Perhaps not, but it may well have been one factor. That change seems to be robust, as their performance relative to other provinces continued to rise in the 2015 PISA.

You make some similar observations about Finland. I agree 100%. One must be cognizant of what is actually being measured and what a ranking, or change therein, might actually signal. One must understand the business of PISA as a lagging indicator.

For the sake of efficiency and unambiguous communication please explain how OECD Pisa sum up the education performance of Canada, a country of 10 provinces with functionally distinct education systems, in three numbers? You are guilty, as are many others, of treating these numbers as if they measure. Pisa (Andreas Schleicher) has relied upon journalists and social scientists to sell the wares for him and his masters, the OECD & the edu-tech giants.

Quoting figures from Pisa as if they are similar to readings from a ruler without mentioning ERROR is a fundamental mistake.

Reblogged this on kadir kozan.

Greg,

When you refer to “some people are not keen on the findings of Pisa at all. On social media I often see it dismissed, particularly in response to any evidence I present from the programme.”

clearly you are referring to the Parental Alliance for Choice in Education blog. http://www.paceni.wordpress.com

I must offer a fact to readers of your blog which they may consider for themselves. You were presented with a link to a paper critical of Pisa and invited to respond with evidence defending them against the charges. You have, to date, not done so.

The paper has been sent to many psychometricians, mathematicians, psycholigists and other academics including Dr. Matthias von Davier, principal research scientist in the Research & Development Division at Educational Testing Service. At ETS, Dr. von Davier manages a group of researchers concerned with methodological questions arising in large-scale international comparative studies in education. He has developed commercially available software for analyses with the Rasch model, with latent class analysis models, and with mixture distribution Rasch models. Matthias knows what he is talking about.

The paper has also be sent to William Stewart of the Times Educational Supplement (TES)

I invite you, once again, to read and respond to the paper below.

https://paceni.wordpress.com/2016/12/04/why-oecd-pisa-cannot-be-rescued-by-ets

It will interest you and followers of your prolific blog to know how Matthias von Davier replied (Hint: the answer does not lie in Rasch or any 2 or 3 parameter IRT model) but first I await your acceptance of the invitation.

Sorry but I’m not referring to the Parental Alliance for Choice in Education. I don’t actually recall being asked for a response about this but I do get a lot of correspondence and so I’ve probably forgotten.

Are you going to offer a reply to the paper given that the subject matter is a direct unequivocal criticism of OECD Pisa

I don’t know. I haven’t read it yet. It depends if I get around to it. Why don’t you post a blog about it?

Are you suggesting that I reply to an article posted on my own blog? Instead of spending time avoiding the issue why don’t you just publish your analysis of the paper? You will have to confront your resistance to accepting the fundamental flaws of OECD Pisa sooner or later Greg. Do your best.

Sorry. I didn’t realise it was on your website. I decide my own agenda. Thanks.

Excellent and thought-provoking piece of writing. See also the below article cautioning those who would simply make Australia copy Finnish practices and expect growth in test scores:

http://www.smh.com.au/comment/finlands-pisa-status-should-not-guide-australias-bid-to-excel-in-education-20160913-grf643.html

Pingback: Is too much choice stressing you out? | Filling the pail

Pingback: Educate Together and the march of progressive education | educationandstuff

Pingback: Useful bits and pieces – A Chemical Orthodoxy

Pingback: Greg Whitby’s rear view mirror | Filling the pail

Pingback: Back to the future with Ken Boston and Jordan Baker – Filling the pail