So ‘post-truth’ is the word of the year and we all want to claim it. I wrote a post where I used it in its original sense – to discuss the kind of politics that fueled the rise of Trump, Brexit, Corbyn, Syriza. What does it mean? It means a world of relativism where no authority is held above any other. It means a world of fake news where demagogues announce revelation to their disciples.

It was only a matter of time before ‘post-truth’ would be deployed in an attempt to win arguments by casting opponents as on a par with Trump. This is exactly what has happened in a recent AARE blog post. Here, we find Trump and Teresa May’s grammar schools all parceled-up with the proposed phonics check for Australia and those rotters who had the temerity to trash-talk educational research on social media.

These things aren’t entirely the same.

For a start, education research has to acknowledge it’s own responsibility for post-truth relativism. Post-modernist and post-structural theory are relativistic philosophies that cast doubt on the notion of truth. Pandora’s box has been opened.

And we have to ask who the truth-sayers are. Education is fundamentally about teaching kids things. So why does so much education research dodge this discourse and claim that nothing can be fixed in the classroom until we fix poverty? I would love to address poverty and inequality. But I also think that we can do useful stuff in the classroom.

So let’s consider this: What is post-truth?

Is it those punks who gatecrash the party and challenge traditional education research?

Or is it writing about the PISA data in order to utterly dismiss it as in the AARE blog? Is it using this data to make an argument about equity that the data doesn’t support? Is it post-truth to ignore the biggest story of all in the PISA data – that a greater use of inquiry learning is associated with worse PISA science scores – in order to try to make political points?

Perhaps post-truth is characterising those who disagree with you as being racists because they happen to point out that a country that was behind Australia in the last TIMSS assessment, and that has fewer resources at its disposal, has now outperformed Australia?

Is it post-truth to note that, following the introduction of a phonics check in the UK, reading comprehension improved – a simple empirical fact? Or is it post-truth to dismiss the idea of a phonics check as being about controlling teachers?

This weekend, I was fortunate enough to have an op-ed that I wrote with Jen Buckingham of the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) published in The Sunday Telegraph in Sydney. The headline ended-up being a bit mangled but it was essentially a guide for parents as to what to look for in Year 4 and it included lots of solid, practical advice.

Despite being left-of-centre politically, I found common cause with someone from a free-market think-tank. Why? Because we happen to agree on some practical strategies that it might be useful to share. Is this post-truth?

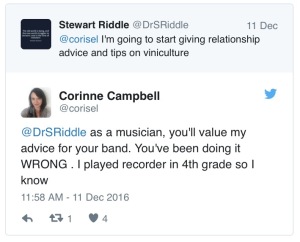

Or is the response post-truth?

Why this trash talk? Why this dismissal? Is this an engagement with the truth?

For what it’s worth, Jen Buckingham has a PhD in literacy, the area that she focused on in the article. I do not have a PhD but I am researching the area of cognitive load as it applies to science education. I also happen to be my school’s research lead and I am head of maths from prep to Year 12. This is why I wrote some fairly tempered, prosaic comments about science and maths.

I ask you to consider this: Who is giving you the truth? Who is interested in the truth? Who is post-truth?

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Reblogged this on The Literacy Echo Chamber.

Is there any way of accessing this article without subscribing?

Many thanks?

Maureen

I’m afraid not. Sometimes, you get access the first time you click through but you won’t on any subsequent clicks. Sorry.

Hi Greg–this interview with Pasi Sahlberg on Finland’s drop is interesting: http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/whats-behind-finlands-pisa-slide

He points to the drop in pleasure reading and increased screen time amongst Finnish boys as a big reason–Finland is the only country in which girls outperform boys in all areas, including maths and science. You may remember from the PISA chart that “being a girl” was an even greater detriment than inquiry learning, so Finland has overcome this, but their boys are underperforming (which makes one wonder why schools would ever want to add MORE screen time by forcing students to use devices to complete schoolwork).

Regarding inquiry learning, Sahlberg is neutral, but does say that Finland’s response is going to be to try to engage students more by increasing the amount of inquiry learning–ie, if education is more “fun” for all, then student motivation will increase.

So, if I understand this correctly, a decrease in student reading for pleasure (and thus adding knowledge to long-term memory, increasing emotional intelligence, adding to vocabulry, etc.) linked to more distractions/screen time is answered by using a pedagogy which “engages” but doesn’t provide a base of knowledge in long-term memory. Seems like somthing there won’t work….

Since we’re discussing post-truth, one of the most significant things about Sahlberg’s 200 page book about the reasons for Finland’s educational success is that he never once mentions teaching methods. I suspect that’s because Finnish teaching, at its highest point of success, was very traditional. He himself is on record as favouring enquiry methods in maths.

What’s interesting about this comment by Sahlberg is that the OECD folks completely ignore their own stuff that he is basing this on by promoting more computer-based education. See this from 2009 on student pleasure reading: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/pisainfocus/48624701.pdf

Notice the gender gap for Finland and Estonia? Australia and the US are pretty far down the list overall and both have their gender gaps. I won’t agree with more inquiry learning, but I think he’s on to something here.

Flagged up here, Greg: http://www.iferi.org/iferi_forum/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=688&start=20