You have to feel sorry for the folks at Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). Like pretty much everyone else involved in education, they have swallowed educational ‘theory’ wholesale and think that they can use this to define the best teaching practices. The problem is that they then set out to empirically test this. The wisest educational theorists never expose their ideas to empirical tests.

Let’s recall the way that PISA defines effective teaching:

““In its Analytical Framework (OECD, 2013), PISA defines the three dimensions of good teaching as: clear, well-structured classroom management; supportive, student-oriented classroom climate; and cognitive activation with challenging content (Klieme et al, 2009; Baumert et al, 2010; Lipowsky et al, 2009; Kunter et al 2008).” [my emphasis]

So , in 2012, they decided to examine the relationship between a student-oriented approach to teaching mathematics and PISA mathematics scores. They created a series of survey questions in order to try to measure the level of student orientation. They found that this correlated negatively with scores – the more student-oriented the teaching, the worse the PISA maths result. The graph below gives some idea and a more sophisticated statistical analysis may be found in this paper.

It is clear what they wanted to find – that a more student-oriented approach led to better results. Unfortunately they found the reverse. However, this finding has not been publicised much by PISA. For instance, in their recent guidance for maths teachers it isn’t really mentioned. Instead, the authors tend to focus on the limitations of teacher-directed instruction which, according to their own data, are far less profound than those of student-orientated instruction.

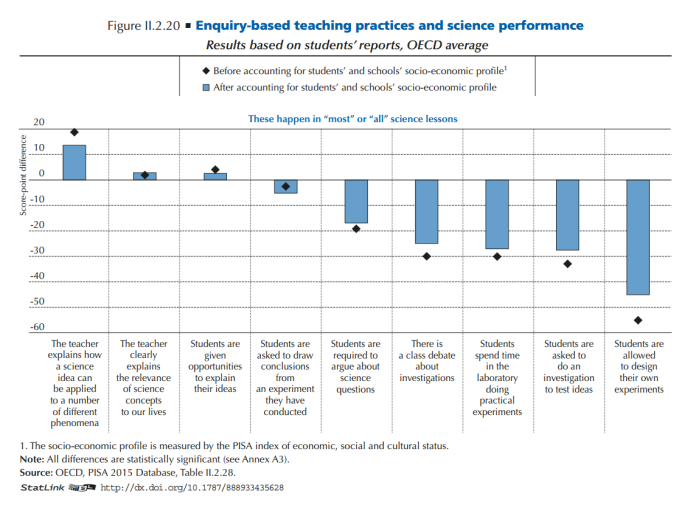

In 2015, the PISA focus shifted to science. This time, they decided to focus on the role of enquiry-based learning. They created a survey to try to capture this and I imagine that, again, they expected to see it relate positively to science performance.

Unfortunately, it did not. PISA’s enquiry-based science construct actually correlates negatively to PISA science scores across nearly all countries that took part. The graph below shows a good summary:

I wonder what PISA will do to publicise this result? It might not have been what they were after but it does seem to triangulate well with a wealth of other evidence that suggests that teacher-directed methods are better than inquiry-based ones. Perhaps this is the finding that will finally move us past the old trope that we need more inquiry-based science teaching in order to better engage students in science and help them apply their understanding. This trope has been rehearsed recently in The Conversation and, incredibly, in The Age after the publication of the above data.

In the words of The Rolling Stones, “You can’t always get what you want. But if you try sometimes, you just might find you get what you need”.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Hi Greg, Don’t hold your breath….at the PISA blog just last month they posted this: http://oecdeducationtoday.blogspot.com/2016/11/new-insights-on-teaching-strategies_23.html

Surely they would have had an inkling of what the new PISA scores were showing about teaching when they put this up…notice the attempt to distinguish between less complex concepts where they acknowledge teacher-directed teaching works…

Well you can’t… unless you’re Avril Lavigne:

Greg, thank you for your post. Although I think you are right what concerns your claims, I would like to add that the graph you presented does not support your arguments, neither would it be in opposition to them, though. The reason for this:The graph is meant to show ONLY practices, which according to PISA are practices of “enquiry-teaching”.

A look at volume II of the report lets me doubt, if the operationalization of the concepts of the 4 teaching methods was a very lucky endavour anyway…

Greetings. @peter4logo

I think you are wrong Pedro. It is hard to see how “Teacher clearly explains …” is enquiry based.

Moreover the order of the criteria is very clearly increasingly inquiry based as it gets worse. So that even if you are right, inside inquiry systems allowing students to plan their own experiments is worse than giving them one to do.

(I suspect an awful lot of it is opportunity cost though. It’s not that doing experiments is bad for students, but that the time could be so much better spent.)

Have you looked at the bottom right section of the graph (which arguably drives the correlation). Do these really look like countries that have a very student-oriented teaching approach? I think there might be something wrong with the construction of this scale?

The paper you link to also points to a negative correlation with teacher-oriented approaches (with a quadratic twist indicating that frequency of intervention is important):

“Teacher-directed instruction (TCHBEHTD) was negatively associated with mathematics performance in 34 education systems and positively in 8, and student oriented teachings strategy (TCHBEHSO) was negatively associated with mathematics in all of the 62 education systems investigated.”

Further the constructivist ‘cognitive activation’ concept, which I’d count as student-focused, was correlated with better performance.

I think that this probably demonstrates one of the problems with survey-based reporting of subjective variables. Nevertheless I do think the correlation is real. Probably not as strong as shown in the data, though.

It helps when one sees the actual questions which are used to produce these variables. Sometimes it looks credible, sometimes it doesn’t seem to correlate well with common use of terms referenced and sometimes as with “cognitive activation” it’s unlikely two randomly picked teachers in adjacent classrooms would extract the same meaning from that phrase, and if they happen to do so and to report approximately the same value on the corresponding variable, it’s just as likely that one is “constructivist” and the other “traditional” as that both teach by the same philosophy. I think there is far too much traffic nowadays in saying Hey, Philosophy X uses word Y and word Y is correlated by survey data with strong scores, so that means X is right! No. If you want a positive correlation of philosophy X then give a short description of the meaning of the term and ask point-blank if a teacher claims to subscribe to that philosophy and incorporate into their classroom practice. Yeah, that would not be perfect. But it would give a far closer approximation to the truth than picking words that one or another philosophy would like to arrogate as solely their own domain. Code actual practice and profession, not vague terminology that can be read as platitudes about teaching.

Pingback: Has Eric Mazur read the PISA reports? | Filling the pail

Pingback: How goals affect your teaching style | Filling the pail

Pingback: PISA data on discipline | Filling the pail

Pingback: Die Belehrungsspiele aus dem Haus der kleinen Forscher « Salman Ansari

Pingback: The bad ideas holding Australia back | Filling the pail

Pingback: The best way to teach | Filling the pail

Pingback: Half a million hits – my top five posts | Filling the pail

Pingback: The Pendulum | Filling the pail

Pingback: New report might be good for Australian education | Filling the pail

Pingback: The STEM delusion – Filling the pail

Pingback: The Stats Don’t Lie..? | The Indies

Pingback: Issue 17 – The Sydney Institute

Pingback: PISA 2030 – Filling the pail

Pingback: The box of frogs agenda – Filling the pail

Pingback: Bucking the trend – Part II – Filling the pail

Pingback: Path smoothing or challenging maths? – Filling the pail

Pingback: What can we expect from PISA 2018? – Filling the pail

Pingback: No, inquiry learning will not keep kids in maths class – Filling the pail

Pingback: How Andreas Schleicher Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Teacher-Directed Instruction – Filling the pail

Pingback: Another big fail for inquiry learning – Filling the pail

Pingback: USA Today story; another look | traditional math