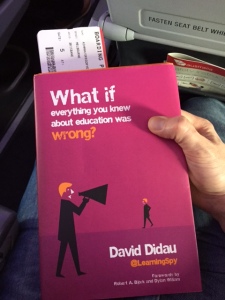

I have finally had the opportunity to read David Didau’s latest tome. I am mentioned in the acknowledgements and a graph of mine is included in the section on differentiation. So you might think it standard for me to now write a few paragraphs about the excellent ideas the book contains or the personable and lively way that it is written. All of this is true. But I’m not going to write that sort of review. Instead, I am going to write about something from the book that made me think and something that I disagreed with.

Liminality of learning

Didau discusses the fact that learning is not performance and that the two have a troublesome relationship. Learning is liminal, Didau claims. it exists in the twilight; on the edge of what is known and what is unknown; where dragons be. Some knowledge is ‘troublesome knowledge’ that is hard to come to terms with. Sometimes, we can help students past the liminal zone by repetition but troublesome knowledge is more of a challenge because it often requires us to revise ideas that we previously accepted. This is what constructivists often suggest before prescribing strategies that don’t solve the problem.

This concept of liminality is key. I tend to see learning through the theory of cognitive load; an interaction between the environment, the working memory and long-term memory; a system mediated and constrained by the limited capacity of the working memory. And a question arises here; should we therefore reduce the cognitive load in tasks to an absolute minimum? The most troublesome aspect of cognitive load theory is the concept of germane cognitive load; the load that leads to learning. It is troublesome because it makes the theory unfalsifiable and so John Sweller now recommends avoiding it in explanations.

It is interesting that germane cognitive load sits in the liminal shadows; precisely the point that Didau would wish us to focus on.

My own view is that we usually underestimate the cognitive load in the tasks that we present to novices and so, as a general rule, reducing it is a good idea. I am not a fan of the notion that children should struggle – I think this unnecessarily increases cognitive load, interacts a great deal with self-concept and can lead to negative attitudes towards a subject. However, I also tend to agree with the quote that Didau attributes to Robert Coe that, “learning happens when people have to think hard.” So there is an uncertain space here that I find interesting.

Learning needs transfer

I disagree with Didau’s definition of learning:

“The ability to retain skills and knowledge over the long term and to be able to transfer them to new contexts.”

The problem is the inclusion of transfer in the definition. It sets the bar too high for learning and implies that anything that does not lead to transfer is not true learning. This idea has been used by educationalists to argue that traditional ‘transmission’ teaching does not lead to ‘deep’ learning and that we need other methods instead. There is usually little evidence supplied that these alternative methods do actually lead to greater transfer but the assertion gets a lot of currency nonetheless.

Transfer is difficult and not even required in many situations. Who regularly solves novel problems? Professional problem-solvers – engineers, plumbers, statisticians – are usually solving variations on well-known problems (thanks to Barry Garelick for shaping my thinking on this). The elevation of transfer tends to do what Didau cautions us against when pursuing taxonomies such as Bloom’s; it devalues ‘lower’ kinds of objectives and makes learning the basics of a subject seem prosaic and unworthy.

I still believe that Willingham’s take on transfer is worth reading.

An odd review

You may think this an odd way to review a book. However, I am hoping that David Didau will be pleased. He spends many pages explaining just how our cognitive biases arise and how they trap us in flawed thinking. I imagine that he would want to get me thinking and to provoke a response to his ideas, even if that response is disagreement.

I spend a lot of time arguing about education and much of this is an ugly parade of fallacy and emotional responses. Didau asks us to take a different path; to accept uncertainty and the fact that we are likely wrong about at least some of what we think. I suggest that this is a noble call. Let us make our disagreements more agreeable.

And get yourself a copy of Didau’s excellent book.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Transfer’ is a big hype in education, indeed. For psychologists it is troublesome also: lots and lots of research, no clear cut results.

Quite another idea about ‘transfer’ is that it is just plain learning in new situations; or better still: all learning is transfer learning. The credits for this idea: Stellan Ohlsson, 2011, ‘Deep learning: How the Mind Overrides Experience. Cambridge University Press.’ http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/psychology/cognition/deep-learning-how-mind-overrides-experience

1) In ‘transfer’ always some extra learning is involved.

The usual implicit idea seems to be that either transfer occurs, or it doesn’t. Call it magic, then. Or just plain BS. 😉

2) The learning of skills always implies ‘transfer’, if you like to call it that. Applying a general rule in a new situation that doesn’t quite ‘fit’. Learning from mistakes. Etcetera.

Ben pointed me to that book and agree it’s great 🙂

Hi Greg,

I like this post a lot and it has triggered my thinking.

I’ve been bashing on the germane load stuff and indeed think the problem indeed is the unfalsifiable aspect. But to me that makes it more interesting because I think the basis for schema building is quite well established. In my view, it therefore should be the focus of (more) research.

To the term ‘struggle’ I would therefore add the importance of timing, feedback etc. An (either intentionally induced or not) struggle needs to be timed right. If you do this in the beginning then I agree that will probably cause overload. After all, there are no prior schemas to use. But after a while (here of course the qualification ‘when do you become an expert’, reversal etc. comes into play as well) schemas can even be counterproductive. Introducing some ‘struggle’ at that point, might cause a conflict, but I’m not sure if the load is too high per se. It also depends on what you do after a struggle, because you’re right that self-concept may be in the way. So the ‘crisis’ should not stay and ‘closure’ is needed. Worked examples and other forms of feedback seem to work well there. Finally, as you know from Renkl’s work, one might have to ‘fade away’ the feedback, to not stay dependent on it. I personally like those attempts (and excellent research) to look at implications for instructional design a lot, and therefore keep picking up on them. You might even see it as a thread through my own PhD research which, granted, could have had a more rigorous design but probably has a stronger ‘tool design’ and naturalistic setting. I must have done something right, given the presence of one of the seminal 2006 KSC paper in the committee 😉

Best wishes,

Christian

PS. I’ll be less snarky 😉

Children learn when they have to think “just hard enough”. If it’s too easy they don’t learn anything. If it’s too hard then they can’t learn anything and it damages their confidence. Pitching it just right is what makes a good teacher which I have just named Goldilocks teaching. Most bad Maths teachers are bad because they give the kids stuff they can’t do.

Also how long can you think really hard for? For hours and hours each day? It’s also about stamina, it’s a marathon not a sprint.

Thanks Greg – I appreciate both the style and substance of your ‘review’.

I do think my take on ‘transfer’ is misrepresented somewhat. In the book I am explicit that I’m not talking about ‘far transfer’ between different domains – I agree this is a fool’s errand. Instead, I’m talking about ‘near’, contextual transfer. Transfer from the classroom to the exam hall for instance. You might be surprised how often students struggle to transfer what they’ve learned from one seat in a classroom to another seat! I think we can agree that everyone needs to be able to transfer knowledge from the context in which they’ve learned to the context in which they’d need to apply it. But do let me know if you don’t agree this point…

On the liminality issue – I try to address the conflict between the need to reduce cognitive load and the need to get students to ‘think hard’ in Chapter 10. I even reference the Willingham blog on inflexible knowledge you reference above. Did you not find my resolution convincing?

I would avoid use of the term transfer entirely in a definition of learning. I understand your caveats but I see the term used to justify so many horrors. And even being able to exactly reproduce something under the same conditions at a later point would be learning as far as I’m concerned.

I’m not disagreeing with you on liminality. I just find it interesting and something that made me think. As you asked, I’m not 100% with you on your resolution of the issue but that’s not because I hold to an alternative; it’s more that I’m still thinking about it all. I think it’s no coincidence that bothersome germane cognitive load slots right into this region.

Fair enough. I used the term transfer because Bjork does. And as far as I can see, being unable to reproduce a thing in a new context is a dubious definition of learning. Isn’t there an irony in you suggesting we avoid the term transform because some people misuse it? I seem to remember you ticking me off for my take on ‘evidence’ 🙂

Ha! It’s not *just* because people misuse it. Although that is a problem. I don’t think it should be in the definition of learning, even with your caveats.

I’m going to blog about struggle, I think. Are you familiar with ‘productive failure’? This is something that is affecting my response.

BTW I like your treatment of novices vs experts. It’s a clear treatment of an issue that confuses many.

Pingback: What is ‘transfer’ and is it important? | David Didau: The Learning Spy

didau does indeed seem to be loading the dice

with the reference to “transfer” here.

if “write (thoughtfully) about something

you disagreed with” is an “odd” reviewing

style? make the most of it! nice piece here.

/*being unable to reproduce a thing in a new context is a dubious definition of learning.*/

“learning” is too general a thing to have “a” definition.

but consider, say, “learning” a piece of music.

*many* players will find themselves unable to

“transfer” certain aspects of their practice-playing

to performance-playing (say)… and for *many* reasons.

to suggest that such players haven’t “learned” their bits

seems way out of line with my idea of “learning”.

it feels to me somehow like the “transference” questions

belong to a “meta” level (“learning about learning”).

not that “meta-learning” isn’t an interesting subject…

*what* it isn’t, is the-same-thing-as “learning” itself

(so why put it into a “definition”?).

“The most troublesome aspect of cognitive load theory is the concept of germane cognitive load; the load that leads to learning. It is troublesome because it makes the theory unfalsifiable and so John Sweller now recommends avoiding it in explanations.”

This is interesting. I’ve always framed Germane load as relating to ideas about ‘Depth of processing’. The simple example I use when talking to teachers about Germane cognitive load is the difference between a word search (which requires very superficial structural processing) and a crossword (which requires more semantic level processing). At the very least, Germane load might be thought of as the opposite of Extraneous load – i.e. beyond the intrinsic load imposed by a task (the sheer number of new elements, etc), the elements of a task which help focus students on rehearsing and automating the new schema (as opposed to interfering with it). I wonder whether, even if it causes problems for Cognitive Load Theory, it might still be a helpful distinction for teachers seeking to apply ideas about working memory to teaching.

Can you point to anything I could read where Sweller has rejected this idea of Germane load.

Pingback: De positie van het Platform O2032 over kennis | onderwijs_2032 science check