I recently read a post in which a senior member of staff described the process of book sampling in his school. Ideas like this spread like wildfire, especially when broadcast via the internet and by someone of such influence. Soon, everyone might be doing it.

It is worth noting that the blog comes from the UK where the pressures are different than other countries. The schools’ inspectorate there, OFSTED, sets the agenda for schools. Even if OFSTED do not ask for a certain practice, schools may adopt it, thinking that OFSTED would approve of it or under the mistaken impression that OFSTED have mandated it. This is perhaps exacerbated by the tendency for OFSTED inspectors to work with schools as consultants.

However, OFSTED can never be a good reason to adopt a particular approach. The only justifiable reason would be that it improves the quality of education; that it enhances learning. Book sampling as described seems to place onerous marking expectations on teachers and so there would need to be a clear benefit to it.

Research versus accountability

One key problem with book sampling is that a good research tool may not operate well as an accountability tool. For instance, imagine we conducted some research and found that the best teachers tended to spend more time standing at the backs of their classrooms. This observation might have some validity in helping to identify the best teachers. However, once teachers knew that managers were looking for this then even the weakest ones would start standing at the backs of their classrooms when being observed. This is a version of Goodhart’s law which is often paraphrased as:

“When a measure becomes a target it ceases to function well as a measure”.

We may protest that we are offering helpful, low-stakes feedback rather than holding teachers to account. Yet it is hard to interpret critical comments from a senior member of staff in any other way.

A poor proxy

It also seems to me that the quality of marking in an exercise book is a poor proxy for what students have actually learnt. This is even more pronounced in subjects with a large practical component such as PE or Drama because book work is only relevant to a part of the intended curriculum. There is research that the quality of feedback influences learning but this isn’t the same thing at all.

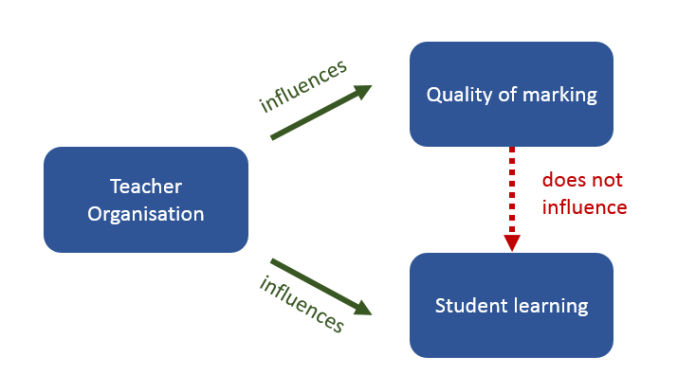

What if we conducted a sample and found a correlation between the teachers whose classes gained the most on external measures and our judgement of the quality of marking? Would this be convincing? Well, it would be circumstantial evidence but it would not imply cause. Perhaps the more effective teachers are better organised and therefore better able to implement the policy? The cause would then be teacher organisation and marking and learning would be two different effects of this. Improving the quality of a particular teacher’s marking would have little to no impact on student learning.

What is good marking?Up to this point, we have assumed that we know what high quality book marking looks like. Usually, this is defined in terms of adherence to a school marking policy. Yet is it hard to trace a through-line from good educational research to the codes, multi-coloured pens, boxes and formalisms adopted by many schools.

If you consider what good quality book marking should achieve then you would perhaps arrive at a list like this:

- Provides useful feedback to the student

- Provides useful feedback to the teacher

- Is positively affective – makes the student feel that his or her work is valued

There are much more focused ways of providing feedback to both students and teachers than through the ritual of taking-up and writing in exercise books. You can use self and peer assessment in class before the lesson has finished. You can use a hinge point question in the middle of the lesson and reteach a concept if it is misunderstood. You can ask a question and get students to write their answers on a mini-whiteboard, immediately assessing what they can do and absolving the teacher of the task of writing the same thing in 30 books. If you want to assess an essay then get students to do this on paper and just take that up like you would for a test.

Although a small delay in feedback might sometimes be beneficial, I am aware of no studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of a smorgasbord of feedback that is given two weeks after the fact when the work has moved on to something else entirely. I doubt this sort of thing has much of an effect even if you ritually require the students to write a prose response. Yes, we should perhaps regularly revisit concepts but this would be better done by a recap or a quiz in class.

Homework is a particularly invalid thing to assess because we have no way of controlling the conditions under which it was done. Middle class students may get help and support from their parents that disadvantaged students don’t receive. Homework assessments would therefore reinforce a bias against the disadvantaged; a bias already identified in teacher assessment.

However, if all we wish is for our students to feel that their work is valued then we can periodically take-up exercise books to just read and sign. We can show we value homework by simply checking that it has been completed (perhaps at the start of the lesson) or by using the products of that homework in the following lesson.

A lazy teachers’ charter?

You might be feeling a little uncertain at this point. If we let teachers off-the-hook on the whole-school marking policy then won’t they just be lounging around drinking instant coffee and eating biscuits all day?

Book marking probably has a very low impact. Effective feedback should be specific and targeted rather than a diffuse mass of colours and codes imposed across subject boundaries. Freed from onerous marking policies, teachers could perhaps adopt more regular in-class assessment that focuses on the particular issues identified within that subject. They could spend more time analysing this data and looking for between-class differences that might identify more and less effective ways of teaching a concept. They could spend time feeding this quality information back into lesson and unit planning.

I reckon that would be better.

I have just made very similar points in my exit interview. I am an English teacher leaving the profession after 7 years this Christmas. The marking workload is unmanageable and I feel that spending 10 minutes in lesson peer and self assessing has as much if not more impact than the two hours of evening spent marking one class set of books with symbols and highlighters etc.

Interesting. I wpuld question your statement about the validity of assessing homework. It is true that there is an element of uncertainty about provenance of work, but in my experience this was easy to spot and did not invalidate the process of assessing homework. Maybe our students were more honest than some.

How do you know about the times you didn’t spot fake homework?

On a slightly related note, during one book scutiny, to avoid teachers cherry picking the best children’s books from HA MA and LA, names were picked at random from the register. A colleague’s picks happened to all be LA children and she was criticised for not having enough differentiation in her class. Neither system is perfect.

Pingback: When Things Go Mad: The Destructive Power of Ideas | SurrealAnarchy

Hi Greg,

Thank you for a good post on an extremely important topic for teachers (and pupils).

For many years I’ve been someone advocating that, here in England, the expectations for marking were far too onerous, complex, time-consuming – and I have responded on many a forum to suggest to teachers that they ask their senior leaders for the ‘time-management studies’ for the schools’ marking policy. Of course I know that these don’t exist – or, if they do, I’m certainly not aware of them. My rationale was to point out that teachers shouldn’t just ‘do’ what they were instructed to do – and if it the expectation was unreasonably time-consuming and/or unreasonably detailed, that teachers should professionally draw attention to this and question the expectations and the rationale. They should argue their case openly and professionally – even commit it to paper as a report.

Sadly, what I know for a fact has happened in at least some cases, is that some teachers get very good at being formulaic and efficient at ‘being seen’ to fulfil the marking policy so they do the multiple colours, specific feedback according to the learning intentions, complete the criteria ladders, do two stars and a wish – or whatever. This then sets a precedence. Because some teachers can manage this, why can’t all the teachers on the staff? The reality is that because the marking takes so long, very often the actual CONTENT, the expression of the pupil as an individual, the essence of the writing for example, is somehow missed.

An astute Year Six boy once said to me that his teacher, ‘..isn’t interested in what I have to actually say in my writing, he’s only interested in the structure of my writing…’ This was a result of all our emphasis in infant and primary education on ‘genre writing’ – which was a national target, and became a national measure – the opposite of what you have highlighted above – ‘measures’ and ‘targets’ work both ways in their influence. The pressure was on Year Two teachers of six and seven year olds to teach various genres for writing at a time when teachers’ time might have been better spent on the ‘basics’ which are not simple basics, as you know, they are complex basics – such as teaching the very complex English alphabetic code, the skills of reading, spelling and handwriting – and solid sentence structure and punctuation. Instead, because children take part in national assessment for genre writing, that is what dominated lesson time.

Further, it is only just recently that the Department for Education in England has removed the notion of ‘levels’ in Key Stages One and Two. Although teachers got used to this assessment system such that some now feel deprived of what they are used to, what happened is that the notion of ‘levelling’ using the grading system of numbers and letters (e.g. 4c, 4b, 4a – showing gradations of any one level) grew from being perhaps a summary level once a term, or half-yearly, or annually, to something which became a weekly piece-by-piece level. The children themselves were involved in knowing these ‘levels’ – and pity the poor children in each class that were languishing at the lower levels – now paraded all over the display boards in ‘rockets to the moon’ to reach specific, displayed curriculum targets. Some children’s rockets never left the ground – and how mortifying that must be.

By the way, now I visit schools and the displays with the main targets on might be described on the posters as ‘Non-negotiables’ – it is chilling quite frankly. The notion of ‘non-negotiables’ for the teachers to teach have become the ‘non-negotiables’ for the children to learn. And this is in infant classes – not just for older pupils.

But there is a reverse side to this, and that is neglect of acknowledging pupil’s work. I think it is very valid indeed for teachers to mark quickly with a tick, a short phrase of encouragement (or disappointment if appropriate), a star, a smiley face (as appropriate for age) when teachers’ time is short. This may well be balanced/complemented by professional feedback to an individual, a group, a whole class in a formative way. Not marking pupils’ efforts is not acceptable – I should think it is pretty soul-destroying for many pupils – and as a mother of four children (now all adult of course), I can describe their frequent dismay at apparent lack of interest, or failure to read or note, work of that may have taken them considerable effort.

Another downside is mini whiteboard work which is not fit-for-purpose when this resource is used to avoid marking, or for a subject which needs to have pupils’ work in an accurate written format. I am thinking of my field in particular – which is phonics – and for which we need to have a record of children’s own knowledge and skills for formative reasons and to track and monitor them as individuals. Over and again I witness very dry phonics lessons conducted on mini whiteboards. I see children with exemplary behaviour sitting on carpets, doing their utmost to write neatly on whiteboards, graphemes, words, a sentence or two, but so much is ‘missed’ by the teacher, incorrect letter formation, no particular support, or tracking, or even intrinsic satisfaction. Nothing remains of the lesson to follow-through. Nothing remains to share with other teaching professionals – or to share with home – or for coordinators or senior managers to review. Using whiteboard markers as the dominant handwriting tool in basic skills lessons is also not fit-for-purpose for handwriting – which should be an integral part of basic literacy lessons. All the pupils wipe off their boards at the end of the lesson (often on their sleeves) – hey presto – no marking requirement. Not much satisfaction for the kids either, of their own efforts.

In summary, I’m very, very sympathetic with the marking expectation which has become ridiculous in England over a number of years – exacerbated by book scrutinies and high-pressure, high-stakes Ofsted inspections.

Greg, you and some other great bloggers are at the leading-edge of influencing others as individuals and as institutions. Let’s bring back common sense but not neglect to mark as a ‘swing’ from years of over-marking.

Finally, I appeal to teachers at least in primary, to mark with far fewer words but to do so in high-quality school handwriting. When I look at marking in schools, teachers’ handwriting nowadays is often really poor – including when scribing for infants. I’ve even seen teachers do giant, scrawly ‘ticks’ all over very carefully presented children’s work. Get a grip.

Perhaps younger teachers nowadays are already a product of the mini whiteboard generation!

I was considering a return to teaching last night and came across the post you describe. I was instantly reminded that the reality at the chalk-face is that, as a profession, teachers are not empowered to do ‘what works’ but instead ‘what looks good’.

Needless to say, it put my current dissatisfaction at work into perspective. If I’m asked to do something here that adds no value, I will be applauded for refusing and drawing attention to it. My output gets checked as part of the process, but no-one trawls through the stuff generated in the course of my work (unless things go wrong and there is good reason to believe that my approach is the cause).

In short, I concluded that the classroom is unlikely to be the right place for me right now.

Pingback: The problem with book monitoring | David Didau: The Learning Spy

Pingback: Work Sampling – another passing fad? | A few thoughts on education

Completely agree with your point about keeping essays separate from exercise books. I would add that they are usually best done in class, under test conditions. Then you actually find out what your pupils can do.

I’ve always thought that ticking and flicking once a week was more than enough to cover the three main points you listed of good marking.

I’d love to see some urgent education research into this, I suspect that that heavy marking has little effect, it could save millions of man-hours not to mention careers, marriages and peoples sanity.

Pingback: Learning reviews: an alternative to work scrutiny? | must do better…

Pingback: Course Correction. The leadership path is never straight. | headguruteacher

Pingback: The people who’ve influenced me in 2015 | headguruteacher

Pingback: 200,000 | Filling the pail

Pingback: Useful bits and pieces – A Chemical Orthodoxy